In this post, I will present how I improved an ETL process to be more than 4x faster using the same resources. While the old architecture used Python threads, the new one used task queue architecture to be more reliable and scalable. So, I will explain how we can improve a legacy code and speed it up by only modifying the architecture to run the code.

Almost 10 years ago, I was hired to improve a system and train a team of engineers in Python and scalable systems. The company had an ETL process to provide financial information for the finance team. The ETL was composed of the crawler, the parser, and the normalizer. The crawler’s primary responsibility was crawling finance data on our partners’ websites, which were protected by a username and password. The parser converted CSV, HTML, and JSON data and saved the result in our intermediate database. The last step, the normalizer, summarized the data using some keys and sent it to the system where the finance team could access it.

The main problem was that the old system took more than 8 hours to complete this entire process. This was unacceptable since the crawler had to start after midnight to collect all the previous day’s data and finish before 8 a.m. when the finance team was ready to discuss the details and take action.

Besides being slow, the old system didn’t have any observability tools, and it had poor log quality.

Throughout my career, I have seen many systems in this situation, and I have also seen many teams and companies decide to rewrite the entire system from scratch. I do not think rewrite is the best approach, at least not before understanding exactly where the problems are. In my experience, whenever a team decides to rewrite a system from scratch, they spend a lot of money and do not finish with a much better system.

Money is not infinite, and I prefer keeping costs as low as possible. So, I dove into the system and discovered that the problem was not the code itself but the architecture to run it. Then, I will show in this post all the issues and how we can resolve each by improving the architecture.

This post is organized as follows: The ETL section explains how to download and release the data we need. The Old solution describes how the old solution was implemented and its problems. The New architecture section explains the new solution and highlights how to resolve all the issues in the old solution. The section Results presents the new solution winnings. The section Can we optimize more? describes one more optimization that we could do and why I decided not to do that. Finally, the section What can we do differently? describes other solutions and the reasons not to use them.

This post is organized as follow: The ETL section explains the process we need to handle the download and release of the data we need. The Old solution explains how the old solution was implemented and the problems with it. The New architecture section explains the new solution and highlighted how to resolve all the problems in the old solution. The section Results presents the new solution winnings. The section Can we optimize more? describes one more optimization that we could do and why I decided to not do that. Finally, the section What can we do differently? describe other solutions and the reasons to not use them.

The ETL

As mentioned earlier in this post, the ETL was composed of 3 main parts: 1) Crawler, 2) Parser, and 3) Normalizer. The crawler was responsible for:

- Login to websites

- Navigate the website and fill in some fields: Sometimes, we can use a seamless approach, and for others, we need a browser to interact with our partners’ websites.

- Download the reports(20K in total); files include: HTML, CSV, JSON

- Save the data in the database

This is a basic crawler process, but we had some additional constraints:

- Only four simultaneous requests to the same sub-domain: This is to not flush our partners with many connections as a Denial-of-service attack.

- Pre-determined IP: Our patterns block connections that are not made from our IP, so I needed to find a way to distribute the crawler horizontally.

The parser worked in the downloaded report and extracted all the information to be stored in a better format. Finally, the Normalization step summarized the data to be released to the finance team.

The desired output was a report that our finance team could access daily during the morning meeting to check and plan actions.

Old solution

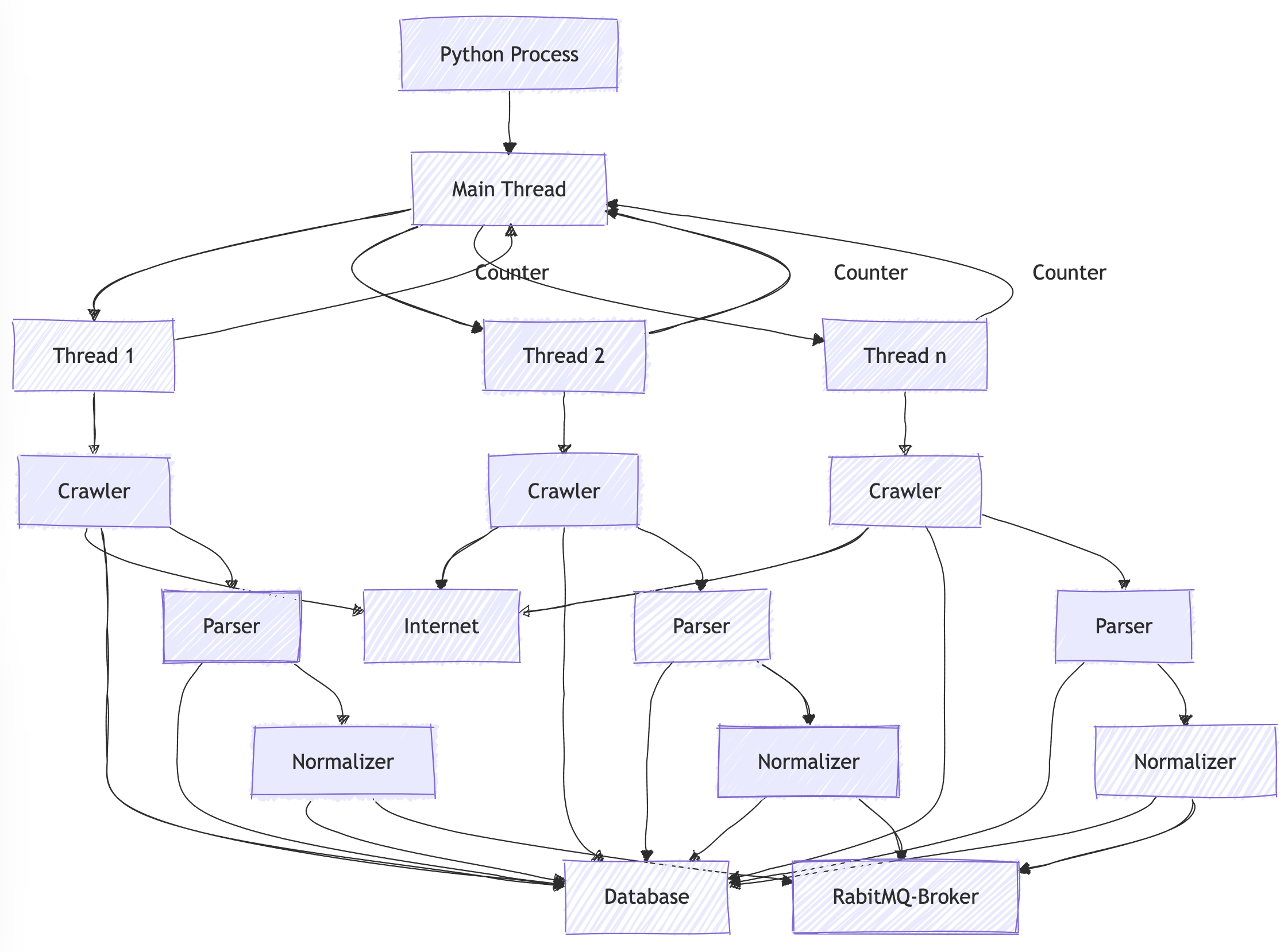

The old architecture consisted of a main Python process that distributed the 20K reports we needed to crawl in many threads. Some variables were shared between these threads to ensure no more than 4 simultaneous requests were made to the same subdomain. Frequently, this resulted in a deadlock, and the ETL didn’t finish. Also, this solution didn’t provide enough observability, reliability, and scalability.

This solution did not provide good observability because it did not have a way to check the system’s health or which reports were processing or downloading correctly in real-time.

Furthermore, this solution wasn’t reliable because the crawler frequently ended up in a deadlock state. Also, this solution was not thread-safe: The shareable variable to control the concurrent domain access was updated without proper handling of simultaneous access. Besides, when a crash happened in a thread that was not properly handled, the variable was not updated, and other threads could not download from a domain since the system showed that the domain was at full capacity when it was not. The consequence of these problems was that the data was not ready to be consumed at the correct time, which created many business problems for us.

Also, this solution wasn’t scalable because a main Python process created many threads in the system without an easy way to distribute the crawler horizontally. Since the network is unreliable, this solution provides a weak way to retry after an error and recreates retry policy capabilities present in open-source libraries.

One main problem is not the threads in Python since any Input/Output calls releases the Global Interpreter Lock for other threads run. It still doesn’t take advantage of a multicore machine, but at least a thread does not block other threads during I/O calls. The main problem is that all the threads are attached to the main process. So, we do not have a way to scale it horizontally. In addition, we do not have a way to observe what is happening while processing a specific report.

The other main problem is that the system does not have a clear Separation of concerns. Even though we have 3 distinct steps: crawler, parser, and normalizer; All of them were coupled together, which makes the scalability difficult. The requirements and way to scale a crawler differ from a parser’s. While a crawler needs to handle network calls and retry on fails, the parser contains business logic that could be constantly updated.

Besides all these deep technical problems, this solution presented a more business-related problem. We did not have a way to reprocess a report that had already been downloaded. For instance, if we updated the parser or normalizer code after running the entire process, we could not trigger only these because the whole system was coupled. So, we needed to run the crawler even though we already had the report downloaded.

The chart below represents this old architecture. It is a little confusing because it is precisely what it was. It was a sequential process that crawled, parsed, and normalized the data, one step after another. Each step saves the result in the database, also called the next step.

The new architecture resolved the problems described here without rewriting the crawler, parser, and normalizer code.

New Architecture

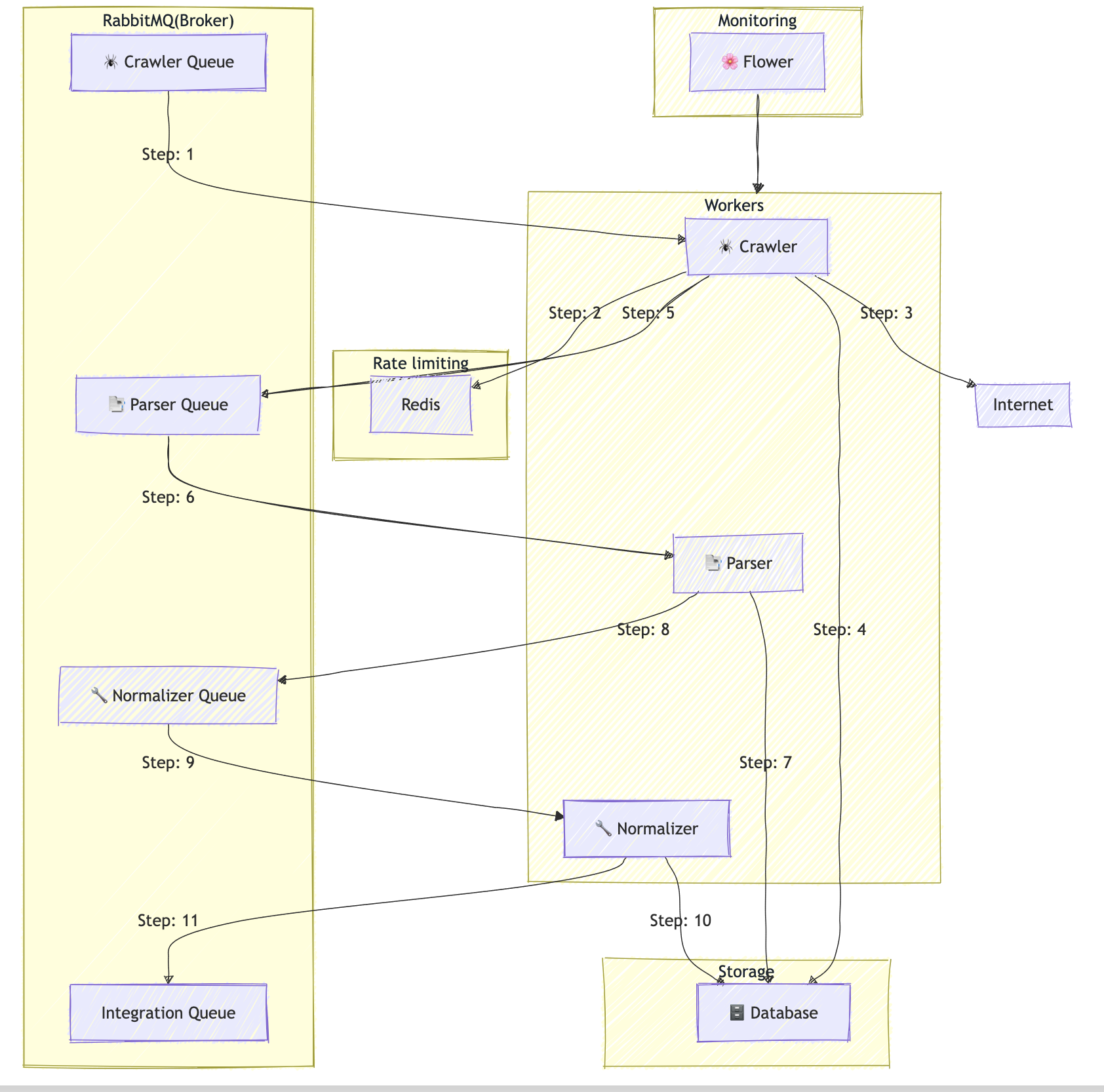

To handle all the problems described in the previous section and to improve observability, reliability, and scalability, I created a new task queue architecture using Celery as the distributed task queue framework, RabbitMQ as the broker, Docker as the container solution, Redis to control the concurrency access in domains, and Flower to monitor all the workers on Celery.

The new architecture is composed of 3 queues. One queue is to crawl messages, one queue is to parser the data, and the other one is to summarize the data. The decision behind this is to separate responsibility and facilitate scalability and observability. Since we use different queues, we can easily add more workers only where needed. The crawler step consumed the most time, so we needed to add more workers.

In addition to the crawler queue, to allow us to scale the crawler horizontally, I added a proxy through which all the connections to our partners should pass. This was necessary because our partners need to know our IP address.

To resolve the concurrency limit by domain, I added a counter in Redis per domain, essentially a rate limiter. So, before the worker starts the crawler, it checks the counter in Redis and proceeds if it is not in the maximum allowed. It is crucial to highlight here that this check and increment was made in a thread-safe way and an atomic operation. This ensures we will not have any problem with concurrency access in these variables.

The chart below represents this architecture. I also highlighted each step when we need to download a report.

Results

It’s essential to highlight that rewriting any code related to the crawler, parser, or normalizer steps wasn’t necessary. I only needed to modify the system’s architecture. With all the improvements cited above, the entire process was reduced from 8 hours to less than 2 hours with the same resources, which is more than 4 times faster.

The new architecture allows us to reduce this time even more when needed by adding more workers. Since 2 hours was enough time for us then, I decided not to add unnecessary workers and save more money.

The new architecture also allows us to run each step separately. Therefore, we can easily update the parser and normalizer codes and run the latest ones without re-running the crawler to get the data. This represents an economy in terms of time and money for the company.

Can we optimize more?

One extra layer that could help us is to add a DNS server to resolve the domain names. The effort for it would not pay the winnings, so I decided not to do that and keep this as a possible follow in the future(It was never done because we did not need this optimization).

What can we do differently?

At that time, the team I mentored was composed only of engineers. So, this team created and maintained the entire code, crawler, parser, and normalizer. The architecture with task queue and Celery worked well in this scenario. If the company decides to move the parser and the normalizer to a less technical team and focus more on the business, we could use Apache Airflow on these steps. However, the company had no plans to do that.